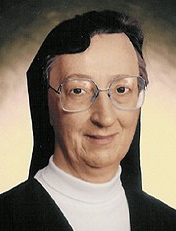

Margaret John Kelly, D.C., Ph.D.

Chapters she contributed to A Concise Guide to Catholic Church Management (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria, 2010)

Reviewed by Mark F. Fischer

The first, fourth and fifth chapters in the Concise Guide are by Sister Margaret John Kelly, a Daughter of Charity who serves as executive director of the Vincentian Center for Church and Society, under whose auspices the Concise Guide was compiled.

1. Leadership

Chapter One, entitled “Leadership,” is an application of Robert Greenleaf’s “servant leadership” concept to church management. Kelly is an enthusiastic advocate of servant leadership, the view that the leader serves followers by enabling them to achieve their goals and develop their potential. She identifies the concept of the servant leader with Jesus Christ and recommends the servant leader style to church managers.

Within the chapter, Kelly considers other styles of leadership described by management experts, which Kelly terms the “authoritarian,” “participative,” and “laissez-faire” styles. She concedes that, “For special situations it may be appropriate to adopt the authoritarian or laissez-faire style,” but insists that “the servant-leaders would seldom call on these” styles (16).

Why does the servant leader model eclipse other models? Kelly argues that “there is considerable agreement” that servant leadership “draws on and develops the best within individuals and within organizations” (8).

This claim may be over-stated. Kelly quotes Ken Blanchard’s appreciative words about servant leadership but never refers to Blanchard’s influential Management of Organizational Behavior with its concept of “situational leadership.” This is the theory that there is no one preferred leadership style, but rather a continuum of styles, each appropriate depending on the level of the followers’ readiness.

Blanchard would never say, as Kelly does, that the servant leader would “seldom” call on any style other than the servant-leader style. Instead he would say that the wise leader changes his or her style depending on what the situation demands.

Kelly’s chapter on “Leadership” in the Concise Guide corresponds in subject matter to the chapter entitled “The Consequences of Pastoral Leadership” by Michael Cieslak in The Parish Management Handbook. Interestingly, however, the two chapters bear almost no resemblance to each other. Cieslak does not even mention servant leadership, but instead correlates the vitality of a parish to the self-knowledge, maturity, and vision of the priest-leader.

In short, Kelly’s embrace of the servant-leader concept to the detriment of other styles limits the usefulness of this first chapter in the Concise Guide. It might have been fairer to say that servant-leadership is appropriate when followers are well-motivated with a relatively high readiness to do their work.

4. Communication

Kelly’s chapter four is entitled “Communication: The Oxygen of an Organization.” She explains the metaphor by saying that communication, likes oxygen, is “essential for organizational survival” (65). Chapter four is interesting because it devotes as much to non-verbal as to verbal communication. It acknowledges the fact that managers may be weakening or even contradicting their explicit communications with messages they may not even know they are sending. Kelly claims that these non-verbal messages make up “75 to 90 percent of daily communication” (71), and draws readers’ attention to them.

In chapter four, Kelly introduces the specialized vocabulary of non-verbal communication without reference to experts, such as Mark L. Knapp, who first developed it. The reader may wrongly assume that Kelly herself coined terms such as “haptics” (communicative touching), “proxemics” (spatial closeness or distance) and “chronemics” (the timeliness of communication). The neologisms may be irritating, but the words describe behavior that everyone will recognize.

5. Meetings

The last of Kelly’s three chapters is entitled “Meetings.” She says that the chapter “presents an overview of the importance of meetings and some practical means to make them instruments of community-building and organizational strength” (85). The second half of the chapter – the “practical means” – is the richer of the two. It considers the question of when it is appropriate to accomplish a task with a meeting and when it is not.

The sections on “Meeting Planning,” “Format for Agenda,” “Traits” of the good leader and the good follower, “Aids to Participation” and “General Guidelines for Meeting” are brief and to the point.

One shortcoming of the Concise Guide is the absence of any thorough discussion of ecclesial consultation via pastoral and finance councils. No chapter in the Guide is dedicated to them, and even within chapters there are only passing references. Kelly refers to pastoral councils in both her chapters on communication and on meetings, but only indirectly, that is, in the case studies with which the two chapters conclude.

In these case studies, Kelly asks the reader to imagine that he or she is on a pastoral council, but does not explain the Church’s general teaching on pastoral or finance councils or their relevance to parish management. This limits the two chapters and the Concise Guide as a whole.

Despite that, the three chapters by Kelly introduce church managers to the basic themes of leadership, communications, and meetings. While these introductions would not suffice for an MBA-level course, they are well-adapted to a seminary course on parish administration or to a certificate program for parish business managers.

To return to the first page of the review of A Concise Guide to Catholic Church Management, click here.

2 Responses to Kelly